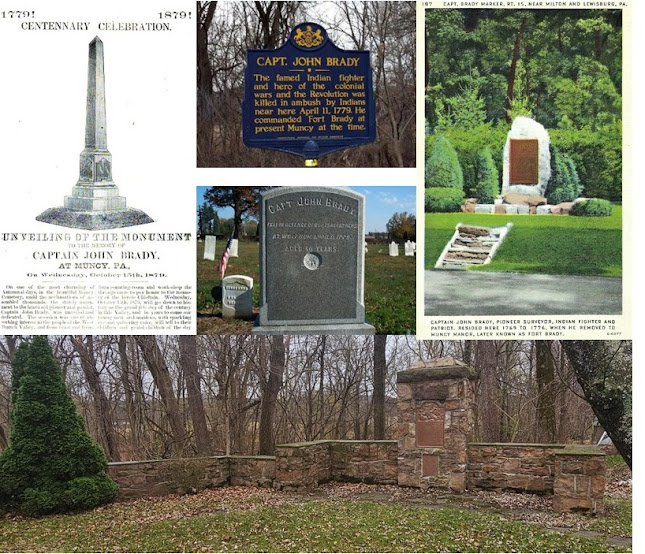

Five Of the Memorial Markers for Capt. John Brady, Rev. War Soldier, Muncy Pa

Capt. John Brady fought with Gen. George Washington at the Battle of Brandywine, serving in the 12th PA Regiment during the Revolutionary War. A soldier, ranger, and scout, he was he was ambushed and killed on his way home from Fort Muncy, April 11th 1779.

From The Brady Family Reunion, 1909:

"John Brady, the second son of Hugh Brady and Hannah Brady was born in 1733 near Newark Delaware where he received a good education and taught school.

He came with his parents to Pennsylvania and soon won the love of Mary Quigley. At twenty two the age of his marriage he was six feet in height, well formed with black hair hazel eyes and a dark complexion.

Fearless, impulsive, and generous, he was one whom friends loved enemies hated. Soon after his marriage, the breaking out of French and Indian war caused him to enlist in the service and his country from the merciless invaders.

Brady was commissioned as captain on July 19, 1763. He served in the Second Battalion, under the command of John Penn, who later became governor of Pennsylvania.

marking where Brady lived before moving to Muncy.

From issues of Now & Then, and Yurchak's book Where the Wigwam's Stood, we find:

Having served the Province of Pennsylvania admirably, Brady was granted a parcel of land of his choosing, something John Penn had granted to all his officers when they left the battalion. Brady's choice was a site near Lewisburg which gave him access to the river and forests to provide for his growing family.

The Pennsylvania Gazette Thu, May 04, 1769 ·Page 8

But the Brady settlement at Lewisburg was only temporary, and he soon moved to Juniata for a short time. He then returned to Lewisburg, building a cabin along the river, in the summer of 1769.

Although, the Brady Family Reunion Book from 1909 describes his land acquisitions slightly differently, and I am uncertain of exactly which details are correct, so I'll simply include both:

"In 1768 urged by the restless mysterious impulse that moulds the destiny of the pioneer of civilization, he re moved his family to Standing Stone now Huntingdon Penn. The following year he again changed his location to a site opposite the present town of Lewisburg Penn. At that period titles to uncultivated lands could be secured by erecting a house and by cutting a few trees by way of improvement. In this manner he took up a vast tract of land on the West Branch of the Susquehanna and had he lived longer he would have been one of the wealthiest men in the state. Owing to the carelessness of those connected with the management of his affairs his family was deprived of much benefit from his exertions."

In 2018 plans for Fort Brady Heritage Park, located at the northwest corner of North Market Street in Muncy, included a public park with trails, interpretive panels and a public archaeological dig, at the former site of Fort Muncy.

Fort Brady In Muncy

"During this period, Brady intensified his interests in surveying. According to Meginness, when the young frontiersman's work took him to Muncy, he was so impressed with "the beauty of the location, the richness of the land, and the charming surroundings," that he decided to settle there permanently."

According to the Brady Family Reunion book, " In 1776 he took his wife and children and belongings to Muncy manor where he built a semi fortified log house known later as Brady's Fort It was a private affair and was not classed among the provincial fortifications. The spot on which it stood is in the borough of Muncy and a slight elevation in a field is pointed to as the exact plot of ground."

J.M.M. Gernerd noted in Now and Then that "Brady's log house and stockade fort was the first improvement on the site of our town." The Samuel Wallis mansion (built in 1769) predates Brady's cabin, and is marked in historical files as "the oldest home in Lycoming County," but its location is about two miles west of the borough.

Brady's home was almost certainly destroyed during the Great Runaway of 1778 - one of the only buildings not burnt to the ground by the Indians during the great runaway was the home of Samuel Wallis. Brady & Capt. John Smith, however, returned to the area in 1779, so it's also likely that they rebuilt Fort Brady after the Great Runaway.

Brady's Service In The Revolutionary War

Brady had joined the Revolutionary Army in the Spring of 1776, and was appointed first major of a battalion headed by a Colonel Plunkett. And soon afterwards, when regiments were formed by Colonel William Cooke, Brady was commissioned captain of one of the companies. The 43-year-old soldier was with George Washington's army when the troops were engaged in battle with England's General Howe at Brandywine in 1777.

Revolutionary War Rolls, Pennsylvania, 11th Regiment, folder 38, page 55. Transcription: 26th February 1777 Received of Mr. Robert Levers Paymaster Sixty Dollars for the use of the sick of the Twelfth Pennsylvania Regiment for which I promise to be accountable to him - Jno. Brady, Capt.

While at Brandywine that frigid winter, Captain Brady contracted pleurisy and was sent home to Muncy to recuperate. On his return in September 1778, the officers of the Twelfth Regiment already had been mustered out. Brady's orders from Washington were to return to the Susquehanna Valley, and help Hartley defend the frontier. He did so, and participated in Hartley's expedition to Tioga.

Attempt At A Treaty With the Indians

The Indians agreed to meet with Capt. Brady and representatives of the settlers at Fort Augusta, in current day Sunbury. It was the summer of the "Big Runaway" and Muncy's families had fled south down the river with only the shirts on their backs.

The Indians who arrived at Fort Augusta appeared in their war costumes, apparently prepared to take a leadership role in the bargaining session. But because the settlers were destitute, they could offer nothing of value to trade with them. The Indians, therefore, retraced their steps up the trail from Sunbury to the Muncy Valley.

Brady suspected that on their return the Indians probably would make their usual stop at Derr's Trading Post, along the river at Lewisburg. Derr kept whiskey by the barrel at the post, and the Indians always stopped there for their "treat." Brady believed it was unconscionable for any settler to offer the Indians whiskey when they were so unwilling to be at peace. He quickly rode up the trail to the trading post. There, an open barrel of rum was near the door. Enraged, Brady overturned the whiskey barrel. The Indians, just as enraged, watched the precious brew spill over the ground.

The winter of 1778 was a bitter cold one, and the Indians were not seen in the Muncy area that season. They had cut their corn fields down, before the harvest, and appeared to have left the area completely, after the incident at Derrs Tavern.

By harvest time in 1778 however, the Indians had reappeared. Colonel Hartley who had managed to get the stockade built at Fort Muncy also provided troops from the militia to protect the harvesters from the Indians. Among these soldiers was James, son of Captain Brady. He was directed by Colonel Hartley to be the sentinel for the reapers.

Early on the Saturday morning of August 8, 1778, "the mists from the river had enveloped the valley with a thick fog. Eager to finish the harvesting, the reapers had set their rifles against nearby trees. They were bundling their sheaves when a band of Indians suddenly encircled them. James Brady, the sentry, was captured first. He was wounded with a spear, and then scalped."

Historians note that Samuel was not only a member of the Brady family, but a redhead - making his scalp a double trophy. As John Brady is described as "of dark haired and of dark complexion", I can't be certain whether that is truth or legend.

Despite being scalped, the 20 year old soldier returned to the fort, asking for his mother. Mrs. Mary [Quiggly] Brady met the canoe carrying her son, and stayed by his side until his death a few days later, on August 13th 1778.

Brady's family returned to Muncy from Sunbury in the Spring of 1779.

Located at current day Industrial Park Rd where it intersects with John Brady Drive, this monument is thought to mark the spot where Brady was ambushed.

Meginness records:

"On the fatal 11th day of April he had taken a wagon and a few men and proceeded to Fort Muncy for the purpose of drawing supplies. After securing the provisions he started the wagon back to his house. He was riding a fine young horse and lingered some distance in the rear of the wagon and guard. Peter Smith, "the unfortunate man" who lost his family in the bloody massacre of June 10, 1778, was walking by the side of the horse and conversing with Brady. He was the same man on whose farm the cradlers and reapers were cutting his harvest at Loyalsock the day James Brady was scalped.

"When within a short distance of his home, instead of following the road taken by the wagon and guard, Brady proposed that they take another road which was shorter. They did so and traveled together until they came to a small stream now known as Wolf run. " Here," Brady observed, "It would be a good place for Indians to hide," when instantly three rifles cracked and Brady fell from his horse dead as the frightened animal was about to run past Smith he caught it by the bridle, vaulted on its back and was carried to Brady's Fort in a few minutes. The report of. the guns was distinctly heard at the fort and caused alarm. Several persons rushed out, Mrs. Brady among them, and meeting Smith coming at full speed and greatly alarmed, excitedly inquired where Captain Brady was. Smith, it is said, replied: "In heaven or hell, or on his way to Tioga" meaning that he was either killed or taken prisoner by the Indians. Tioga was the point they generally made for with their prisoners.

"The wagon guard, with several others, quickly repaired to the place where the firing occurred, and there, as it was feared, the gallant Captain was found lying dead in the road. The Indians, who had no doubt been dogging his footsteps from the time he left his house, were in such haste that they did not scalp him or take any of his effects. It was about midway between Fort Muncy and Fort Brady where they lay in ambush, and so anxious were they to make sure of killing him that they paid no attention to Smith, but all three fired on him at once. And as they knew there were plenty of armed men at both forts, and that they would be pursued at once, they dashed into the bushes and put themselves at a safe distance as quickly as possible. They cared not for his scalp, it was glory enough to know that they had slain the man they all hated and feared."

Meginness further records:

"His daughter, Mary Gray, of Sunbury, who was fifteen years old at the time of the assassination of her father, retained to the last moments of her life (December 3, 1850) a vivid recollection of the startling scenes of that day, and could relate the circumstances with great minuteness. She said that two balls entered his. back between the shoulders, showing that the miscreants fired at him after he had passed their place of concealment. The third shot missed him, if there were three, as it was always claimed; but Smith, in his excited condition, might easily have mistaken the number. Mrs. Gray said that her father carried a gold watch, and his parchment commission as a captain in the Continental Army in a green bag suspended from his neck. These were undisturbed."

Fatally shot, Brady was not scalped, nor was he robbed, which is curious indeed, for an Indian attack. And Peter Smith, who was with him at the time, escaped unharmed.

Letter from Benedict Arnold to John Andre, in which he lays out the terms for selling West Point to the British. It includes the demand that 1,000 pounds sterling (Roughly $250,000 US Dollars in 2021) be given to Samuel Wallis.

Today we know that Samuel Wallis was a spy, in league with Benedict Arnold. Did Brady perhaps suspect this, all those years ago? Was this group of Indians perhaps on a mission, on behalf of Wallis, to eliminate Brady? Was it even Indians who made the shot? Was Brady's death an Indian attack, or a planned assassination, ordered by Wallis? If Brady did suspect Wallis was a traitor, why would he not have shared his concerns with Smith?

The Express, in 1966, printed Hugh Brady's Account of his fathers death, and concluded that it was "never positively known that the Indians did the shooting".

To add to the mystery, in 1926 when an excavation was made for a swimming pool, on the former Wallis property [today Muncy Farms] the body the bodies of three British soldiers an two Native Americans were discovered. [From a talk Brian Barlow gave at the Muncy Historical Society].

The new marker, replacing the earlier, smaller, stone.

"An old comrade who was present at his burial pointed to the site and requested that he be laid by his side. His request was granted, and near by Captain John Brady's grave is that of his friend Henry Lebo. The Lycoming Chapter D. A. R. recently honored his memory by placing an appropriate marker between his grave and that of his faithful comrade."

Installed in 1940

| Dedicated in 1928

| And possibly the man behind Brady's death? |

Marker in Halls Station Cemetery Placed by the Lycoming DAR

| State Historical Marker Placed in 1947

|

Dedicated in 1879

|

DEATH OF CAPT. JOHN BRADY.

Nothing of unusual interest occurred in the vicinity of. Fort Muncy until the 11th of April, 1779, when Capt. John Brady was waylaid and shot by three Indians about one mile east of the fort. Brady had made himself particularly obnoxious to the Indians on account of his activity in opposing them. He took an active part in Colonel Hartley's expedition and attracted the attention of the Indians by his bravery. Having been ordered to remain at home from the Continental Army to assist in guarding the frontier, he was active as a ranger and the savages thirsted for his blood.

His family had returned from Sunbury, whither they fled when the "Big Runaway" took place, and were occupying their fortified house at Muncy. At this place Brady made his headquarters. On the fatal 11th day of April he had taken a wagon and a few men and proceeded to Fort Muncy for the purpose of drawing supplies. After securing the provisions he started the wagon back to his house. He was riding a fine young horse and lingered some distance in the rear of the wagon and guard. Peter Smith, "the unfortunate man" who lost his family in the bloody massacre of June 10, 1778, was walking by the side of the horse and conversing with Brady. He was the same man on whose farm the cradlers and reapers were cutting his harvest at Loyalsock the day James Brady was scalped.

When within a short distance of his home, instead of following the road taken by the wagon and guard, Brady proposed that they take another road which was shorter. They did so and traveled together until they came to a small stream now known as Wolf run. " Here," Brady observed, "It would be a good place for Indians to hide," when instantly three rifles cracked and Brady fell from his horse dead as the frightened animal was about to run past Smith he caught it by the bridle, vaulted on its back and was carried to Brady's Fort in a few minutes. The report of. the guns was distinctly heard at the fort and caused alarm. Several persons rushed out, Mrs. Brady among them, and meeting Smith coming at full speed and greatly alarmed, excitedly inquired where Captain Brady was. Smith, it is said, replied: "In heaven or hell, or on his way to Tioga" meaning that he was either killed or taken prisoner by the Indians. Tioga was the point they generally made for with their prisoners.

The wagon guard, with several others, quickly repaired to the place where the firing occurred, and there, as it was feared, the gallant Captain was found lying dead in the road. The Indians, who had no doubt been dogging his footsteps from the time he left his house, were in such haste that they did not scalp him or take any of his effects. It was about midway between Fort Muncy and Fort Brady where they lay in ambush, and so anxious were they to make sure of killing him that they paid no attention to Smith, but all three fired on him at once. And as they knew there were plenty of armed men at both forts, and that they would be pursued at once, they dashed into the bushes and put themselves at a safe distance as quickly as possible. They cared not for his scalp, it was glory enough to know that they had slain the man they all hated and feared.

His death caused much excitement among the few inhabitants along the river, as they all regarded him as an invaluable man in those days of peril, and his loss was well nigh irreparable. His widow was greatly distressed and felt the blow most keenly. Her lot was a hard one. Only eight months before her son James was stricken down by the same bloody hands that had slain her husband.

His daughter, Mary Gray, of Sunbury, who was fifteen years old at the time of the assassination of her father, retained to the last moments of her life (December 3, 1850) a vivid recollection of the startling scenes of that day, and could relate the circumstances with great minuteness. She said that two balls entered his. back between the shoulders, showing that the miscreants fired at him after he had passed their place of concealment. The third shot missed him, if there were three, as it was always claimed; but Smith, in his excited condition, might easily have mistaken the number. Mrs. Gray said that her father carried a gold watch, and his parchment commission as a captain in the Continental Army in a green bag suspended from his neck. These were undisturbed.

When the body was found, strong arms tenderly assisted in carrying it to his late home, where preparations were begun for the funeral. A coffin was probably made of bark. There were no plain or costly burial cases in those days in the pioneer settlements, but the hero of many a well. fought battle reposed as calmly in a bark or deal, board coffin as he would in the most magnificent casket of modern times. His funeral, which took place two days afterwards, was attended by all in the settlement who could get away., All the men bore their arms, for they knew not the moment the lurking foe would assail them. The services were short, for there was no clergyman present to read a prayer or pronounce a fitting eulogy over his rude bier. What brief services took place were conducted by some sturdy friend, whose rifle stood within easy reach. The cortege moved across Muncy creek, up the road, and by the lonely place where he was, instantly stricken down in the prime and vigor of his manhood, to the burial ground on the brow of the hill, within sight of Fort Muncy. There his grave had been prepared. Captain Walker, with a firing squad, was present, and, a salute fitting to his rank was fired over the grave as the coffin was lowered to its last resting place. There were few dry eyes at that burial scene over 112 years ago. All felt that a friend and protector had been taken and as each man firmly grasped his rifle he resolved that he would never relax, in his efforts to avenge the death of the fallen patriot while war lasted, or the red fox prowled in the forest.

The mourners returned to the saddened home from the lonely grave on the hill. There were no gay equipages or prancing steeds to convey them. Men carried their trusty rifles. Sadness and gloom settled over the Brady homestead at Muncy. The widow, whose cup of sorrow was now full to overflowing, speedily gathered her younger children around her and fled to the home of her parents in Cumberland. county the following May, less than a month after the death of her husband. She had passed through the trying scenes of the "Big Runaway," but now that her husband was gone she could no longer remain in the settlement. Her eldest son, Samuel, the renowned scout and Indian slayer, was a captain in Colonel Brodhead's regiment, and was absent on a western expedition. It. is said of him that when he heard of his father's death he raised his hand and vowed to high Heaven that he would avenge the murder of his father, and while he lived he would not be at peace with the Indians of any tribe. And terribly did he carry out his vow. He slew many and made himself a terror to all redskins on the western borders. Having fully avenged the death of both his-father and younger brother James, and peace, being restored, he died at his home near Wheeling, December 25, 1795.

It was never positively known what Indians were concerned in the death of Capt. John Brady. The secret was profoundly kept and perished with the deaths of those who, committed the atrocious deed. The spot where he was killed is still pointed out. The ground afterwards became a part of the farm of Joseph Warner, and is now owned by Charles Robb, Esq., of Pittsburg, whose ancestors were among the earliest settlers at Muncy, and were there when Brady was killed.

THE BRADY FAMILY.

The Brady family, on account of its patriotism and identification with the stirring times of the Revolution and border wars, has always occupied a conspicuous niche in history, and the heroic deeds and thrilling adventures of its prominent members, if fully recorded, would fill a large volume. Capt. John Brady, second son of Hugh, came of Irish parentage, and was born in Delaware in 1733. He received a, fair education and wrote a plain. round hand, as shown by his autograph now in the possession of the author. He taught school in New Jersey for a few terms before his parents emigrated to the Province of Pennsylvania and settled near Shippensburg, Cumberland county, some time in 1750. He learned surveying and followed it before the Indian troubles became, serious. In 1755 he married Miss Mary Quigley, of Cumberland county. Her parents and relatives were ancestors of the, Quigleys now so numerous in Clinton county. John and Mary (Quigley) Brady had thirteen children, eight sons and five daughters. Two sons and one daughter died in infancy. Samuel, the eldest, was born in 1756. At the time of his birth "the, tempestuous waves of trouble were rolling in upon the infant settlements in the wake of Braddock's defeat," and "he grew to manhood in the troublous times that, tried men's souls."

On the breaking out of the French and Indian war John Brady offered his serv-ices as a soldier, and July 19, 1763, he was commissioned a captain of the Second, Battalion of the regiment commanded by Governor John Penn, and took part in the Bouquet expedition. For this service he came in with the officers for a grant of land, which he selected west of the present borough of Lewisburg.

Meanwhile, moved by the "restless, mysterious impulse that molds the destiny of the pioneers of civilization," Captain Brady had taken his family to Standing Stone, (now Huntingdon,) on the Juniata. There his son Hugh, afterwards major general in the United States Army, and twin sister Jane, were born, July 27, 1768. In the summer of 1769 he moved his family to a tract of land lying on the river opposite Lewisburg, which he had reserved out of the " Officers' Surveys," and there he made some improvements. His profession as a surveyor called him to various places in the valley, and visiting Muncy manor he became impressed with the beauty of the location, richness of the land, and charming surroundings, when he selected a tract, as already stated, and decided to settle there. In the spring of 1776 he erected a stockade fort and soon afterwards took his family to it.

When Northumberland county was erected in 1772, and the first court was held at Fort Augusta in August of that year, he served as foreman of the first grand jury. In December, 1775, he accompanied Colonel Plunkett in his ill-advised expedition against Wyoming. Soon after the breaking out of the Revolution two battalions of associators were raised in Northumberland county, and commanded respectively by Colonels Hunter and Plunkett. In the latter Brady was appointed first major, March 13, 1776. July 4, 1776, he attended the convention of associators, held at Lancaster, as one of the representatives of Plunkett's battalion.

The term of associators for mutual protection ended with a year and nine months' service. After that regiments enlisted for the war were raised. William Cooke was made colonel of the Twelfth, which was composed of men enlisted in Northumberland and Northampton counties. John Brady was commissioned captain of one of the companies, October 14, 1776, and on the 18th of December it left Sunbury to join the Continental Army in New Jersey. When Washington moved his army to the banks of the Brandywine to intercept Howe, Brady was present with his company and took part in the engagement. He also had two sons in this battle. Samuel was first lieutenant in Capt. John Doyle's company, having been commissioned July 17, 1776. John, his fourth son, born March 18, 1762, and then only fifteen years old, was there also. He had gone to the army to ride some horses home, but noticing that a battle was imminent, insisted on remaining and taking part. He ,secured a gun and joined the company. The Twelfth regiment was in the thickest of the fight, and Lieutenant Boyd, of Northumberland, was killed by Captain Brady's side. His son John was slightly wounded, and he fell from a shot in the mouth. The day ended with disaster and the Twelfth nearly cut to pieces. Luckily Captain Brady's wound was not serious. The shot only loosened some of his teeth. As he was suffering from an attack of pleurisy, (from which he never entirely recovered,) he was given leave to visit his home. On the 1st of September, 1778, he reported for duty, but as the field officers of his regiment had been mustered out, and the companies distributed among the Third and Sixth regiments, Captain Brady was sent home by General. Washington's orders, together with Captain Boone and Lieutenants Samuel and John Daugherty, with instructions to join Colonel Hartley and assist in defending the frontier. Brady and his companions reached Fort Muncy September 18th, joined Colonel Hartley, and, as already stated, participated in the expedition to Tioga.

Captain Brady was one of those men to whom Colonel Hunter referred in his letter of December 13, 1778, "who would rather die fighting then leave their homes again." His son John, who took part in the battle of Brandywine, was elected sheriff of Northumberland county in 1794, and was in office when Lycoming county was erected. He died in 1809. The personal appearance of Capt. John Brady has come down to us through tradition. He was six feet in height, straight, well formed, had dark hair and complexion, and hazel eyes.

THE BRADY CENOTAPH.

The little cemetery where he was buried is on the face of the hill near Hartley Hall station, at the junction of the Williamsport and North Branch with the Philadelphia and Reading railroad, ten miles east of Williamsport, and is plainly visible, from the cars as they pass up and down both railroads. At the time of his interment only a few burials, mostly of persons killed by the Indians, had been made there. it is among the oldest cemeteries in Lycoming county, and is still used for that purpose. For many years it was negleited and became overrun with briers and brambles. But of late years it has been neatly kept. It is known as Hall's burial ground and belongs to that estate.

The spot where Captain Brady was laid is a lovely one, and a fine view of the surrounding country is afforded. The public road between Muncy and Williamsport passes the cemetery, and by looking over the picket fence the grave of the patriot soldier can be plainly seen. The grave was not attended for many years and was finally lost eight of. Gen. Hugh Brady, his youngest son, often sought it in vain. At last his daughter Mary, then the wife of Gen. Electus Backus, U. S. A., was made acquainted with it by Henry Lebo, an old comrade and Revolutionary soldier, who was present at the funeral. On his deathbed he made a request to be buried by the side of Captain. Brady, and his request was carried out. Lebo was in the battle of Germantown and was badly wounded. After the war he came to Muncy, married, and for many years kept a public house by the roadside on one of the Hall farms. He had several sons and daughters. Robert W. Lebo, a well known citizen of Port Penn, is a grandson.

Although it had often been suggested that a monument should be reared in honor of Capt. John Brady, a hundred years passed before it was done. Through the untiring efforts of J. M. M. Gernerd, of Muncy, enough money was raised by one dollar, contributions to erect a beautiful cenotaph to his memory in the cemetery, of Muncy, three miles away from the place where the ashes of the hero commingled with the soil. It was formally dedicated and unveiled, October 15, 1879, in the presence of a great throng of people, including many descendants of the distinguished dead. Hon. John, Blair Linn, of Bellefonte, delivered the historical address, in which he recounted the many noble deeds of the deceased, whose grave had remained neglected and unmarked for the full round period of a century. In closing his eloquent oration he used these words:

To Captain Brady's descendants, time fails me in paying a proper tribute. When border tales have lost their charm for the evening hour; when oblivion blots from the historic page the glorious record of Pennsylvania in the Revolution of 1776; then, and then only, will Capt. Samuel Brady, of the Rangers, be forgotten. In private life, in public office, at the bar, In the Senate of Pennsylvania, in the House of Representatives of the United States, in the ranks of battle, Capt. John Brady's sons and grandsons and great-grandsons have flung far forward into the future the light of their family fame.

From far and near, all over this grand valley, the most beautiful to us the sun in his course through the heavens looks down upon, we have come to dedicate this monument to the memory of its pioneer defender - Capt. John Brady.

At thy feet, then, Oh I Mountains of Muncy! thy solemn Red Men fled before the mystic sound of coming civilization; we, before the tramp and tread of States; we dedicate this granite landmark to Brady, the pioneer, the Corypheus here, of title by improvement and pre-emption; a system which began by the rock at Plymouth, and will continue until the last echo of the woodman's axe dies away amid the surges of the Pacific.

In thy bosom, Oh I Valley of the West Branch I we dedicate this memorial to the eagle-eyed sentinel, who one hundred years ago peered through the dusky twilight for thy foes. Here, on these heights, in this holy bivouac of the dead, let it forever stand sentry of his compatriot slain of Antietam, of Fredericksburg, of the Wilderness, of Atlanta, of the mourned battlefields of the war for the Union, whose last "All's well!" is still echoing gloriously through the Republic.

On thy bright waters, Oh! Noble Susquehanna! which mirror in thy winding course so many, many scenes of domestic peace and comfort; so many scenes of Eden-like beauty, rescued from primeval wildness, only listening, in thy quiet course to the sea,

To the laughter from the village and the town,

And the church bells ever jangling as the weary day goes down.

Surrounded by these venerable fathers who have lingered in life's journey to see this happy day; surrounded by the life and beauty of this grand old home of brave sons and patriotic daughters, under the auspices of the Grand Army of the Republic—the "Cincinnati" of the war for the Union-in solemn joy we dedicate this monument to our benefactor. And as we gaze upon it, let us resolve, that as this government came down to us from the past, it shall go from us into the future —a blessing to our posterity, and the hope of the world's freedom.

The ceremonies were opened with prayer by Rev. E. H. Leisenring, after a parade, with music, and were imposing and impressive. The poem was composed by Col. Thomas Chamberlin. It opened with a description of the valley and surrounding mountain scenery, the coming of the settlers, their trials and vicissitudes, the attacks of the Indians, the flight, return, and final death of Brady.

The cenotaph is plain but massive, and is constructed of Maine granite in four handsomely proportioned piece, consisting of a base, a sub-base, a die, and an obelisk, the whole rising to a height of twenty-seven feet and weighing about twenty-five tons. It rests on a solid foundation of masonry hidden from sight by a sodded terrace nearly three feet high, and is in proportion to the size of the circular lot in the center of which it stands. The total elevation of the cap of the shaft is about thirty feet. The date, "1779," is cut about the center of the shaft on the front face, in raised figures; the name, "John Brady," in heavy letters in the die, and the date of erection, "1879," in the center of the sub-base. On each side of the die is a large polished panel, bordered by a neatly chiseled molding. to correspond with the lines of the die and shaft. The faces of the letters and figures are brightly polished, and all other exposed parts of the cenotaph are finely out. Its artistic proportions are pleasing to the eye, and it is much admired by visitors to the cemetery. It cost about $1,600.

In the cemetery at Hall's, where the remains of Brady lie, together with those, of his compatriot and friend, Lebo, granite markers were also placed. They consist of thick slabs, 30x21 Inches, set on bases 14x29 inches, and they are forty-four inches in height. The stones are unpolished, except the fronts, on which the epitaphs are cut in plain letters. The foot stones are in the same simple style without lettering. The money required to erect these markers, about $70, was also raised by Mr. Gernerd by means of an autograph album at twenty-five cents a signature. The inscriptions on these markers read as follows:

Captain John Brady fell in defense of our forefathers, at Wolf Run, April 11, 1779, aged forty-six years. In memory of Henry Lebo, died July 4,1828, in the seventieth year of his age.

There side by side sleep the patriot hero and his faithful friend. Near by stands a lonely pine tree, through whose branches the wind sighs a soft, plaintive requiem for their departed spirits. And notwithstanding more than a hundred years have rolled away since Brady was laid at rest, in this quiet retreat, many strangers and others still visit the spot and stand with uncovered heads in the presence of the dead.

When the widow of Capt. John Brady, bowed down with grief and sorrow, bade adieu to her home on Muncy manor and started for Cumberland county her youngest child, Liberty, born August 9, 1778, at Sunbury, was only about seven months old. She was named Liberty, because She was born after Independence was declared, and was the thirteenth child, corresponding with the thirteen original States. She grew to womanhood, married William Dewart, of Sunbury, and died there, without issue.

Although so overwhelmed with the weight of misfortune which had overtaken her, Mrs. Mary Quigley Brady did not sit down to pine in grief over her hard lot. She was made of sterner stuff, and proved herself a type of the Roman matron of old. Having recovered somewhat from the shock caused by her misfortunes, she determined to return to the West Branch valley and found a home for herself and children on the tract of land granted to her husband west of Lewisburg through the "Officers' Surveys," for his services in the Bouquet expedition. With this resolve she left the home of her parents the subsequent October and performed the wonderful feat of riding on horseback, carrying her young child, Liberty, and leading a cow, from Shippensburg to, her Buffalo valley home. How the other children got through is unknown, but they did and joined their resolute mother. There she lived until October 20, 1783, when she died, aged forty-eight years. A marble tablet in the cemetery at Lewisburg, with an appropriate inscription, marks her grave.

=============================

On the 11th of April, Captain John Brady who, it will be remembered, commanded a so-called fort bearing his name and located near the mouth of Muncy Creek, was killed by the Indians, scarcely a quarter of a mile away from its protecting walls. It had become necessary to go up river some distance to procure supplies for the fort, and Captain John Brady, taking with him a wagon team and a guard, went himself and procured what could be had. On his return in the afternoon, riding a fine mare, and within short distance of the fort, where the road forked, and being some distance behind the team and the guard, and in conversation with a man names Peter Smith, he recommended Smith not to take the road the wagon had, but the other, as it was shorter. They traveled on together, until they came near a run where the same road joined. Brady observed, 'This would be a good place for Indians to secrete themselves.' Smith said 'Yes.' That instant three rifles cracked and Brady fell. The mare ran past Smith, who threw himself on her and was carried in a few seconds to the fort. The people in the fort heard the rifles, and seeing Smith on the mare coming at full speed, all ran to ask for Captain Brady, his wife along, or rather before the rest. Smith replied, 'In heaven or hell, or on his way to Tioga,' meaning that he was either killed or taken prisoner. Those in the fort ran to the spot and found the captain lying in the road, his scalp taken and his rifle gone; but the Indians had been in such haste that they had not taken his watch or shot-pouch. Rapine followed throughout the settlements. Isolated murders and cases of pillaging were almost numberless and larger strokes of savage fury were not infrequent. Several of these murders occurred at Fort Freeland. By May so great had become the sense of insecurity that the greater number of the people of Buffalo Valley had left. Colonel Hunter had poor successes in recruiting companies of rangers, as so many of the able-bodied men of the settlements were preparing to enter the "boat service" [the convoying of General Sullivan's commissary up the North Branch]. By the last of June he had only thirty men, exclusive of those at Fort Freeland and with General Potter, who was at Sunbury. By the late part of July the troops had all left Sunbury to join General Sullivan. Northumberland County was left in a deplorable condition, with no forces but the militia and fourteen regulars under Captain Kamplen. Almost every young man on this part of the frontier had engaged in the boat service, and the country above Muncy was completely abandoned.

On the 11th of April, Captain John Brady who, it will be remembered, commanded a so-called fort bearing his name and located near the mouth of Muncy Creek, was killed by the Indians, scarcely a quarter of a mile away from its protecting walls. It had become necessary to go up river some distance to procure supplies for the fort, and Captain John Brady, taking with him a wagon team and a guard, went himself and procured what could be had. On his return in the afternoon, riding a fine mare, and within short distance of the fort, where the road forked, and being some distance behind the team and the guard, and in conversation with a man names Peter Smith, he recommended Smith not to take the road the wagon had, but the other, as it was shorter. They traveled on together, until they came near a run where the same road joined. Brady observed, 'This would be a good place for Indians to secrete themselves.' Smith said 'Yes.' That instant three rifles cracked and Brady fell. The mare ran past Smith, who threw himself on her and was carried in a few seconds to the fort. The people in the fort heard the rifles, and seeing Smith on the mare coming at full speed, all ran to ask for Captain Brady, his wife along, or rather before the rest. Smith replied, 'In heaven or hell, or on his way to Tioga,' meaning that he was either killed or taken prisoner. Those in the fort ran to the spot and found the captain lying in the road, his scalp taken and his rifle gone; but the Indians had been in such haste that they had not taken his watch or shot-pouch. Rapine followed throughout the settlements. Isolated murders and cases of pillaging were almost numberless and larger strokes of savage fury were not infrequent. Several of these murders occurred at Fort Freeland. By May so great had become the sense of insecurity that the greater number of the people of Buffalo Valley had left. Colonel Hunter had poor successes in recruiting companies of rangers, as so many of the able-bodied men of the settlements were preparing to enter the "boat service" [the convoying of General Sullivan's commissary up the North Branch]. By the last of June he had only thirty men, exclusive of those at Fort Freeland and with General Potter, who was at Sunbury. By the late part of July the troops had all left Sunbury to join General Sullivan. Northumberland County was left in a deplorable condition, with no forces but the militia and fourteen regulars under Captain Kamplen. Almost every young man on this part of the frontier had engaged in the boat service, and the country above Muncy was completely abandoned.

Fall of Fort Freeland.-All things conspired to give the Indians opportunity for a more than usually effective blow. It was directed against Fort Freeland, and that stronghold was capture on July 28, 1779.

A number of British officers and soldiers were with the besieging party, the advance portion of which made it appearance on the 21st. The whole force consisted of about three hundred men. Colonel Hunter writes upon the 28th,-"This day, about twelve o'clock, an express arrived from Captain Boone's mill, informing us that Freeland's Fort was surrounded; and, immediately after, another express came, informing us that it was burned and all the garrison either killed or taken prisoner; the party that went from Boone's saw a number of Indians and some red-coats walking around the fort, or where it had been. After that, firing was heard off towards Chillisquaque. Parties are going off from this town and from Northumberland for the relief of the garrison. General Sullivan would send us no assistance, and our neighboring counties have lost the virtue they were once possessed of, otherwise we should have some relief before this. I write in a confused manner. I am just marching off, up the West Branch, with a party I have collected. “A few days before the capture, Robert Covenhaven went up as far as Ralston (now), where he discovered Colonel McDonald's party in camp. He returned to Fort Muncy (Fort Penn) and gave the alarm. The women and children were then put in boats and sent down, under his charge, to Fort Augusta. He took with him the families at Fort Meninger, at the mouth of Warrior's Run; but Freeland's Fort being four and a half miles distant, they had no time to wait for the families there, but sent a messenger to alarm them.

****************************************

His body was brought to the fort and soon after interred in the Muncy burying ground, some four miles from the fort (now Hall's station, P. & E. R. B.) over Muncy creek." His grave is suitably marked at Hall's, while a cenotaph in the present Muncy cemetery of thirty feet high, raised by J. M. M. Gernerd by dollar subscription, attests the lively interest still felt by the community in one who devoted himself to the protection of the valley when brave active men and good counselors were needed. Of his sons, Capt. Samuel Brady, a sharpshooter of Parr's and Morgan's rifles, fought on almost every battlefield of the Revolution, from Boston and Saratoga to Germantown, can speak of his deeds as a scout and Indian fighter Western and Northern Pennsylvania, which West Virginia and Ohio attest. To the Indian he became a terror, and he fully avenged the blood of his sire shed at Wolf run, on the West Branch of the Susquehanna, that beautiful day in April, 1779, at the bloody fight of Brady's Bend, on the Allegheny, where, with his own hand, he slew his father's murderer and avenged his brother James, the "Young Captain of the Susquehanna," in a hundred other fights. Of his second son, James, killed by the Indians at the Loyal Sock, whose career bid fair to be as brilliant as his elder brother's but unfortunately cut off at his commencement. John, who, when but a boy of fifteen, going with his father and oldest brother to the battlefield of the Brandywine to bring back the horses, finding a battle on hand, took a rifle and stepped into the ranks and did manful duty, and was wounded. He is said to have served with Jackson at New Orleans in the War of 1812. William Perry Brady served on the northern borders in the same war, and at Perry's victory at Lake Erie, when volunteers were called, was the first to step out.

Hon. John Blair Linn, at the dedication of the Brady monument in 1879, one hundred years after the death of John Brady, said: "To the valley his loss was well, nigh irreparable; death came to its defender, and ‘Hell followed hard after. In May, Buffalo Valley was overrun and the people left, on the 8th of July Smith's mills, at the mouth of the White Deer Creek were burned, and on the 17th Muncy valley was swept with the besom of destruction. Starrett's mills and all the principal houses in Muncy township burned, with Fort Muncy, Brady and Freeland, and Sunbury became the frontier."

"History of that part of the Susquehanna and Juniata Valleys, Embraced in the Counties of Mifflin, Juniata, Perry, Union and Snyder In The Commonwealth of Pennsylvania." In Two Volumes, Vol 1 Philadelphia: EVERTS, PECK & RICHARDS 1886, pp 97-99

He was married to Mary Quigley.

Parents of 4 sons: Samuel Brady James John William

Family links: Parents: Hugh Brady (1709 - 1779) Hannah McCormick Brady (____ - 1776)

Spouses: Mary Quigley Brady (1735 - 1783)*

Children: Mary Brady Gray* Mary Clemson Brady (1752 - 1819)* John Brady (1761 - 1809)*

Siblings: John Brady (1733 - 1779) Samuel Brady (1734 - 1811)* Joseph Brady (1735 - 1781)* Hugh Brady (1738 - 1782)* James Brady (1753 - 1818)*

Burial: Hall Station Cemetery Pennsdale Lycoming County Pennsylvania, USA

Captain John Brady By Belle McKinney Hays Swope

John Brady, the second? (First) son of Hugh Brady and Hannah Brady, was born in 1733 near Newark, Delaware, where he received a good education and taught school. He came with his parents to Pennsylvania, and soon won the love of Mary Quigley At twenty-two, the age of his marriage, he was six feet in height, well formed, with black hair, hazel eyes and a dark complexion. Fearless, impulsive and generous, he was one whom friends loved and enemies hated. Soon after his marriage the breaking out of the French and Indian war caused him to enlist in the service and defend his country from the merciless invaders. On July 19, 1763, he was commissioned Captain, Second Battalion of the Pennsylvania Regiments, commanded by Governor John Penn and Lieutenant Colonels Asher Clayton and Tobias Frances. In 1764 he received his commission of Captain in the Second Pennsylvania Battalion, in Colonel Bouquet's expedition west of the Ohio, in which campaign he participated, and he took part in the land grant to the officers in that service during the year 1766. He was actively engaged against the Indians who made desperate slaughter in Bedford and Cumberland Counties, and killed many of the settlers. When his regiment reached Bedford, the officers drew a written agreement, wherein they asked the proprietaries for sufficient land on which to erect a compact and defensible town, and give each a commodious plantation on which to build a dwelling. Captain John Brady was one of the officers who signed this petition. In 1768, "urged by the restless, mysterious impulse that molds the destiny of the pioneer of civilization," he removed his family to Standing Stone, now Huntingdon, Penn'a. The following year he again changed his location to a site opposite the present town of Lewisburg, Penn'a. At that period titles to uncultivated lands could be secured by erecting a house, and by cutting a few trees by way of improvement. In this manner he took up a vast tract of land on the West Branch of the Susquehanna, and had he lived longer, he would have been one of the wealthiest men in the state. Owing to the carelessness of those connected with the management of his affairs, his family was deprived of much benefit from his exertions.

In 1776 he took his wife and children and belongings to Muncy manor, where he built a semi-fortified log house, known later as "Brady's Fort." It was a private affair and was not classed among the provincial fortifications. The spot on which it stood is in the borough of Muncy and a slight elevation in a field is pointed to as the exact plot of ground. After Northumberland county was formed, Captain John Brady was appointed foremen of the first grand jury, and served in many such capacities afterwards.

Not slow to respond to the call to arms in defense of home and the independence of the nation, he marched to the front in some of the bloodiest engagements of the War of the Revolution. He fought with Washington at Brandywine, where his two sons, Samuel and John were with him, and he was wounded in the mouth. The loss of some teeth was the result, but he was disabled by an attack of pleurisy and sent home.

In 1775 Colonel Plunkett made his famous expedition to the Wyoming valley, and John Brady was one of his ablest assistants. The Connecticut settlers claimed under their charter the territory of the province of Pennsylvania as far south as the 41st degree of latitude, which ran a mile north of Lewisburg, and determined to enforce their rights. In 1772 a party of them reached the present town of Milton, but were driven back by Colonel Plunkett. The settlers were not subdued and the contest was waged many years. They advanced to the Muncy valley and made a settlement where the town was later located. In order to punish the intruders for their presumption in occupying this part of the West Branch region, blood was shed and lives were lost.

John Brady was a surveyor of land in Cumberland, Buffalo and White Deer valleys, and in the possession of his descendant Mrs. Charles Gustav Ernst, nee Mollie Brady Cooper, of Punxsutawney, Penn'a, is a surveyor's guide book, entitled "Tables of Difference of Latitude and Departure," for navigators, land surveyors, etc., "compiled at the instance of a committee of the Dublin Society, by John Hood, Land Surveyor. Published in Dublin in 1772." She has also an account book which has on the inside of the leather cover the words printed in ink, "John Brady, his book, Cumberland County, 1765."

On March 3, 1776, he was commissioned Major of the battalion commanded by Colonel Plunkett, and on October 14, 1776, Captain in the Twelfth regiment of the Pennsylvania line, commanded by Colonel William Cooke, whose two daughters became wives of two of Captain John Brady's sons. In 1778, on the invasion of the Wyoming valley, he went with his family to Sunbury, and September l, 1778, returned to the army. In the Spring of 1779 he received orders to join Colonel Hartley on the West Branch, and on the 11th of April, 1779, was killed by a concealed body of Indians. He had taken an active part in efforts to subdue their atrocities, and his daring and repeated endeavors intensified their hatred and desire to capture him resulting so fatally on that spring-time morning. With a guard and wagon he went up the river to Wallis' to procure supplies. His family was living at the ' Fort" at Muncy during the winter and early spring, and from his home to the provision house was only a few hours' ride. On their return trip, about three miles from Fort Brady, at Wolf Run, they stopped to wait for the wagon, which was coming another way. Peter Smith, whose family was massacred on the 10th of June, and on whose farm young James Brady was mortally wounded, was by his side. Captain John Brady said: "This would be a good place for Indians to hide." Smith replied in the affirmative, when the report of three rifles was heard, and the Captain fell without uttering a sound. He was shot with two balls between the shoulders. Smith mounted the horse of his commander and escaped to the woods unharmed, and on to the settlement. It was not known what Indians did the shooting, but proof was evident that a party had followed him with intent to kill. In their haste, they did not scalp him, nor take his money, a gold watch, and his commission, which he wore in a bag suspended from his neck, his dearest earthly possession. Thus perished one of the most skilled and daring Indian fighters, as well as one of the most esteemed and respected of men, on whose sterling qualities and sound judgment the pioneers of the entire settlement depended.

Carried to his home at Fort Brady, which he built, and is now within the borough limits of Muncy, his heroic little wife looked the second time upon the blood stained form of one of her family, her son James having met the same fate on the 8th of August of the preceding year.

Laid to rest on the hillside, where few interments had been made, his grave was well nigh forgotten. and weeds and briars hid the lonely mound of earth, until the spot was identified through the efforts of a grand-daughter of Captain John Brady, Mrs. Backus, wife of General Electus Backus, U. S. A. Prior to 1830 at Halls, a heavy granite marker was erected bearing the inscription:

Captain John Brady

Fell in defense of our forefathers

at Wolf Run, April 11, 1779

Age 46 years

An old comrade who was present at his burial pointed to the site and requested that he be laid by his side. His request was granted, and near by Captain John Brady's grave is that of his friend Henry Lebo. The Lycoming Chapter D. A. R. recently honored his memory by placing an appropriate marker between his grave and that of his faithful comrade.

A hundred years after his death, through a dollar subscription fund, raised by Mr. J. M. M. Gernerd, a monument was placed in the cemetery at Muncy, and unveiled October 15th, 1879. The date 1779 is On the front of the shaft, the name "John Brady" in the die, and the date of erection 1879 in the sub-base. The cost was $1600.00, and that of the slab in the burial lot at Halls $70.00, the latter also due to the untiring energy of Mr. Gernerd, by an autograph subscription at twentyfive cents a signature. In closing his oration at the unveiling of the monument, Hon. John Blair Linn, of Bellefonte, Penn'a, said: "To Captain Brady's descendants, time fails me in paying a proper tribute. When border tales have lost their charm for the evening hour; when oblivion blots from the historic page the glorious record of Pennsylvania in the Revolution of 1776, then and then only will Captain Samuel Brady of the Rangers be forgotten. In private life, in public office, at the bar, in the Senate of Pennsylvania, in the House of Representatives of the United States, in the ranks of battle, Captain John Brady's sons and grandsons and great-grandsons have flung far forward into the future the light of their family fame."

Captain John Brady was foremost in all expeditions that went out from the West Branch settlement, and his untimely death was a sore affliction. When the inmates of the fort heard the report of the rifles that ended his life, they, with his wife, ran to ask Smith, who was with him, where he was, and his reply, "In heaven or hell or on his way to Tioga," showed his rapid flight, for he did not wait to see whether Captain Brady was killed or taken prisoner. His was a remarkable career, and death claiming him in the prime of manhood, robbed the earth of one of her strongest sons, and the nation of one of her most loyal subjects, but in the lives and life work of his children, was continued and completed the blessings and benefits to mankind commenced so unselfishly by him.

Mary Quigley Brady

And now came the test of character which proved Mary Quigley Brady a true woman, a consecrated mother, and one of the bravest heroines of history. At the age of twenty the little Scotch-lrish maiden, with large bright blue eyes, linked her fortune with that of John Brady, big, broad-shouldered and handsome, coming scarcely above his heart in height, yet as fearless and noble as he. It was considered a good match. The Quigley and Brady families were of the same faith, the same social standing, and each in comfortable circumstances. Until 1768 she either lived with her father or near him, and enjoyed the privileges of her girlhood home as in days gone by. With true wifely devotion she followed her husband's restless footsteps to the West Branch valley, and on the tract of land which was given him for provincial services, she began her work of training her sons and daughters for the duties of life, and nobly she fulfilled her mission.

Churches there were none, hence the instruction given was largely due to her zeal, while the father cultivated the soil and protected the little home won by his military daring. Later, on their productive land near Muncy, she encouraged her sons In the tilling of the soil, but their souls longed for broader fields of activity and usefulness, and the battle cry rather than the reaper's song brought a responsive echo. "Her sons, beside their fine mental endowments, were perfect specimens of humanity, and the average height of the six boys when grown to manhood was six feet. "

When Captain John Brady joined Washington's army, he took with him his sons, Samuel and James, the first winning an officer's commission soon after he was twenty years of age, and James becoming a sergeant before he reached the age of eighteen.

Day after day during those perilous times, Mary Quigley Brady kept her younger sons employed on the farm, ever on the alert against the surprise of the Indians. Her position being wearing and dangerous, her husband was given leave of absence while the army was in winter quarters at Valley Forge. In 1778 her son James was mortally wounded by Indians, dying four days after Liberty, her youngest and thirteenth child, was born. As independence had just been declared, she called her Liberty, and was very anxious lest the minister who christened the child would not know whether, from the name, it was a boy or girl. He baptized it Liberty Brady, and happily applied the feminine gender in his prayer for its welfare, and relieved the mother's anxiety. As there were thirteen states, and this the thirteenth child, the name was fitting and well chosen, and has descended to each successive generation of the Brady family. After the death of her husband in 1779, with her cup of sorrow filled to the brim, turning from his new made grave, beside which slumbered four children, she fled with her nine remaining sons and daughters to the home of her parents in the Cumberland valley, along the Conodoguinet Creek. She spent the months from May until October with her father and mother, returning to the Buffalo valley with her family, and settled on the original tract of land presented to her husband by the government. Many men would shrink from such a perilous undertaking in those days of bloodshed, knowing not in what bushes might be hiding an Indian who hungered for a scalp to add to his trophies; but her duty to her children led her through all the dangers, and her cheerful courage never flinched, and with her manly sons and helpful daughters she took up the burden of life again in her own home.

When she started from her father's house, her brother, Robert Quigley, gave her a cow, which she led over the hills to the Buffalo valley, carrying Liberty. who was fourteen months old, before her on horseback. Her indomitable perseverance enabled her to reach her destination in safety, but the difficulties, and exposure of the journey were great, and although a vigorous, healthy woman of forty-four, her constitution weakened, and coming to the scene of her heart's deepest sorrow, there was opened for her a trying winter. The season of 1779-1780 was severe, the depths of snow so impassable that intercourse with even their few scattered neighbors was hindered, and some of these were massacred by the Indians in the early springtime.

Many a day her son Hugh walked by the side of his brother John, carrying a rifle in one hand and a forked stick to clear the plow shear in the other, while John plowed. The mother frequently went with them to prepare their meals; in constant peril, but in this as in all the joys and adversities of life, an angel of mercy to them, her death on the 20th of October, 1783, was a personal and grievous loss to each of her children. To them, since the death of her husband, she had given her undivided attention and affection, and for them she had unselfishly labored. She was rewarded for her care, as shown by a remark made by her distinguished son, General Hugh Brady, "My brothers lived to be men in every sense of the word, at a period when the qualities of men were put to the most severe tests." She was proud of her children, and modest in receiving praises for her share in their training, but her satisfaction in seeing them leaders in warfare, at the time America's most eventful history was enacted, more than repaid her. They were not only skilled in military tactics, but their alertness and ingenuity in planning attack made their names and deeds linger in every heart and on every tongue.

Mary Quigley Brady died at the age of forty-eight years, after a lingering illness due to exposure, and is buried at Lewisburg.

A long while back, I read an account in "Now and Then" that brougth up suspicion about Peter Smiths role in the ambush... Have you seen that article ?

ReplyDeleteNo - but I own the bound volumes and will look for that! I admit that I had questions about Smith's account. Interesting!

Delete