|

| The Twiggs & Clark Murder Case In Danville, 1858 |

Mary and William both repeatedly proclaimed that they were falsely accused by prejudiced neighbors. And perhaps they were. Although found guilty at trial, there was little real evidence of their guilt. The minister attending to them throughout their confinement appears to have believed Clark was guilty, but that Twiggs was innocent. The jury however, did not agree.

"Mrs. Mary Twiggs was recently hung at Danville, Pennsylvania, for the supposed murder of Mrs. Clark. The papers state public opinion was divided on her guilt. It is bad enough to hang any person, but to hang a woman whose offense is not so clear, but that public opinion is divided with reference to her guilt, is an act of reckless barbarism, sufficient to disgrace any people." - The Wisconsin Democrat

The Clark & Twigg Families

William J. Clark came to Danville with his wife Catherine and two young children in 1855, to work as a puddler at the Montour Iron Works. A year after Clark came to Danville, in August of 1856, David Twiggs and his family arrived in town, settling in an area of Danville known as "Rudy's Addition". Like many other Irish immigrants, David came to Danville to work at the Montour Iron Mill.

Danville was a bustling, crowded, Industrial town in the 1850s. Immigrants at this time frequently crowded into subdivided homes, it was common for several families to live under one roof. It's thought that the Clarks and Twiggs families shared a home.

In April of 1857, Catherine Ann Clark took her two young children to Philadelphia to visit her family. While she was in Philadelphia, on April 19th,

Catherine Clark arrived back in Danville at the end of April. Shortly after her return, she became ill. She took magnesia, a common tonic of the time, for awhile and when that did not help, a neighbor brought her a home remedy of oil and whiskey.

Still, Mrs Clark did not improve. Dr Simington was summoned, and he diagnosed Mrs Clark with inflammation of the stomach and bowels, prescribing "additional medicine" for her. Mrs. Clark continued to suffer from persistent vomiting and "nervous twitchings". Mary Twiggs helped to care for the ailing woman, running the household and caring for the children throughout Catherine's illness.On May 9th, less than two weeks after first becoming ill, Catherine Clark died. Her infant child, whom she had been nursing throughout her illness, died a short time later.

After Catherine's death, "tongues were wagging" over the conduct of Mary Twiggs and Mr Clark, both now widowed. Soon, with the "gossip mills churning faster than the iron in the mills", Coroner Haas called for an inquest into the death of Catherine Clark. When the cause of death was found to be arsenic, the body of David Twiggs was exhumed, and it was found that he, too died from arsenic poisoning. At the coroners inquest, clerks at the Chalfont & Hughes Pharmacy recalled selling arsenic to William Clark on one occasion, and Mary Twiggs on another.

Based on those findings, 27 year old Mary Twiggs and 22 year old William John Clark were committed to Montour County Jail on suspicion of murder.

Escape Attempts

As was common at the time, the Sheriff and his family lived in the Montour County Jail. The sheriffs wife would do the laundry and serve the meals to the prisoners.

Clark attempted escape first, using a piece of glass and a nail to unlock his shackles. The next morning when the Sheriff and Mrs Young (the Sheriffs wife) brought breakfast to the two prisoners on the second floor, Clark was hiding, shackles undone, behind the door. Clark pulled the Sheriff into the cell, then ran out, bolting the door behind himself, and then locking the sheriffs wife in with Mrs Twiggs.

Clark escaped through a garden, heading towards the Susquehanna River. His plan was to wade across the river to the Blue Hill area of Sunbury. But he didn't get far. He was captured as he attempted to cross an open field. Taken back to jail, he was handcuffed, and his legs were tired securely to prevent another attempt at escape. A search of his cell found a pillowcase containing his shackles, and a round stone that could have been used as a weapon.

Clark stated that he felt that the people of Danville were in such a fervor, they would perjure themselves and say anything to convict him, and that escape was his only option.

Mary did not attempt escape until much later, after William had been hung.

Using a small nail and a chicken bone, Mary attempted to create a hole in the wall of her cell. Her attempt was foiled when Sheriff Young searched her cell and found dirt and stones under her bed. He then had her handcuffed and place in the cell that Clark had previously inhabited.

When asked about her escape attempt, Mary seems to say that God told her to do it . "I doubt you'll believe me, but Saturday night I went on my knees beside the bedside to ask the Heavenly Father if he would help me get out. And then I pulled the nail that was sticking in the wall to hang clothes on, and I went to work. I was so sick I could hardly stand on my feet. I worked as long as I could bear it, and then went and stood by the window. I saw the gallows on the wall by the moonlight and it made me feel so bad that I went back to work again and got several stones loose in the wall before morning. Sunday night I got so far that I could see through the wall. But I didn't succeed, and now I'll not try anymore. If I can't be let out now in a regular way, and if it is the will of Heaven that I should die on the scaffold, I will say no more."

The Trial Of William Clark

The trial began on February 16th 1858. A variety of local families testified of the "trifling informality" between Mary Twiggs and Clark. There was no proof of an affair, only innuendo and assertions that the two were overly friendly. One of the claims was that Mary had placed her hand on the arm of William at a dinner with several others present.

There was no written record of the arsenic purchases, and under cross examination, Robert McCarty admitted he couldn't be certain it was was Clark who had purchased the poison. Arsenic was commonly used for rat control in the 1850s, it would not have been an unusual purchase.

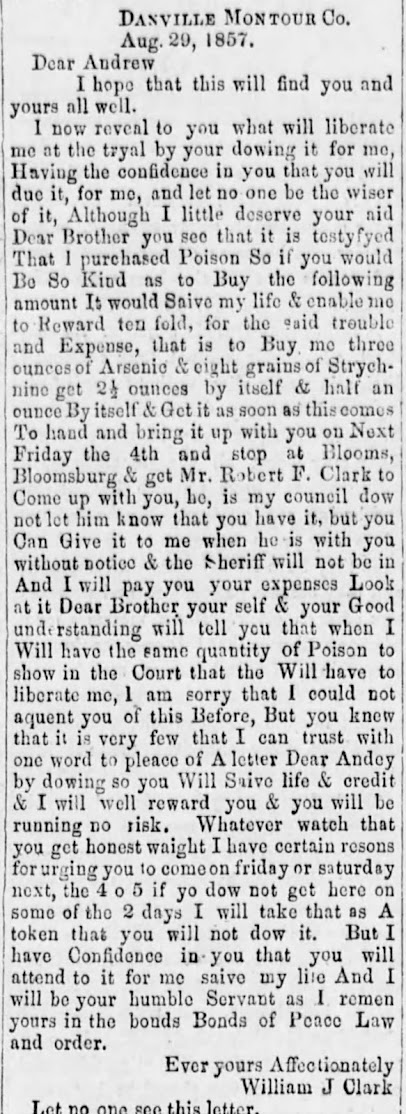

It may have only been the act of a desperately panicked man who feared he would be wrongly convicted, but the request made him look guilty in the eyes of the town, and the jurors.

In a letter to the press in July, Clark suggested that someone else had written the letter to Thompson, in an attempt to frame him.

In the book Instigations Of The Devil, the author includes both the original letter, about the poison, that Clark insists he did not write, and the letter Clark did write, professing his innocence. There is a startling contrast between the two letters. The first is poorly written and full of misspellings. The second letter is written by an educated, well spoken, man. It is difficult to believe that the same man penned both letters.

The Sunbury American, when printing portions of Clarks letter from the pamphlet, remarked:

"The above are a few extracts taken from the declaration of Wm. J. Clark, which we give to you to gratify the curiosity which our readers may have to see what desperate lengths a guilty man may be driven to, to mislead public opinion and to create sympathy for himself...."

Mary Twiggs father, Mr. McClintock, took the stand to say he had been living with Mary and he had never seen anything improper between his daughter and Clark. Thompson Foster took the stand to testify that Clark had wanted his wife examined after her death to prove that she had not been poisoned. Dennis Emery, a coworker of Clark, took the stand to say that David Twiggs had been Clarks helper at the iron mill, and the two appeared to be good friends. Emery described Clark as a peaceful man, affectionate towards his wife. [The Bloomsburg paper printed much of the trial word for word, as did several other newspapers.]

The testimonies regarding Clarks good character were to no avail. It took the jurors just 6 hours to return a verdict of guilty. On 7pm February 18th 1858, a bell in the courthouse tower rang to announce the jury had reached a verdict.

William Clark addressed the court at sentencing, proclaiming his innocence in a long, dramatic speech

"But as I said before, to comment upon my innocence is useless in such a prejudiced community as this." he proclaimed. Later in his speech he pointed to his lips saying "Here are the lips that were never polluted by a harlots kiss" then pointing to his breast "here is the breast on which a prostitute never reposed and" now pointing to his heart, "here is the heart that never beat for a strange woman, and I am innocent of the foul charge. I have nothing more to say now, you can proceed to pass sentence."

The judge replied with his own speech, ending with "and that you be there hanged by the neck until you are dead. And may God have mercy upon your soul."

In July of 1958, the Sunbury Gazette published a portion of a very lengthy letter from Clark, in which he continued to proclaim his innocence. It was a lengthy letter. A Danville paper published the letter in its entirety, selling it as a pamphlet, for 10 cents.

The Trial Of Mary Twiggs

By the time Mary Twiggs went to trial in May of 1858, the murders had been national news. The Danville newspaper reported that the trial "brought many strangers to town".

Again a variety of neighbors testified of the familiarity between William Clark and Mary Twiggs.

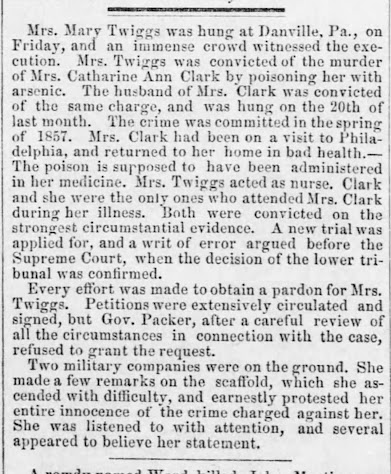

In less than a days time, Mary Twiggs was found guilty of the murder of Catherine Clark. Mary, like William, was sentenced by the judge "to be hanged by the neck until you are dead, and may God have mercy on your soul."

The Execution Of William Clark

The night before his execution, Peter Harder and George Souder volunteered to stay at the jail with Clark. The two men read scripture and prayed with Clark, who repeatedly told them "death has no sting for me, I am at peace with my God." Clark stated that he had nothing to regret, he was an innocent man.

Before midnight, Clark burnt a number of papers he had written.

September 24th 1858 was a rainy, overcast, day, but that did not keep the curious public from flocking to the jail yard to see the gallows being readied. A coffin was nearby on display as well.

Special Sheriff's deputies, with printed badges, had been sworn in for the day. Two military units, The Columbia Guards, and the Montour Rifles, were also on hand to maintain order, and remove the crowd from the jail yard prior to the execution, which was closed to the public.

Clark woke early, prayed with Harder and Souder, then had a breakfast of bread, water, and "panada", a brandy & sugar mixture. He smoked a cigar, wrote out a speech to be delivered on the gallows, and spoke with several visitors.

At 11am Clark was taken to the scaffold. The crowd had been removed from the yard, as the hanging was to be closed to the public. It was however witnessed by a Jury specifically assembled as a panel of observers, along with ministers, physicians, deputies, and reporters.

Clark climbed the stairs to the gallows, and for a full forty five minutes read his prepared remarks, again reiterating that he was not guilty, and that witnesses had lied during his trail. He claimed that McCarty realized he had never sold the arsenic to him, and had recanted his statements.

Clark was firm and unfaltering, until the coffin was brought before the scaffold. At that time, his voice trembled.

In his remarks, Clark stated that his wife refused to take a cup of water from their neighbor, Mrs. McMullen, and hour before her death. He further stated that Mrs. Mullen had made punch for David Twiggs and that a short time after he had drunk it, he began vomiting, continuing to do so until he died.

Clark ended his remarks by thanking his attorneys and ministers, and the Danville newspaper editors, "for not prejudicing my case before trial.".

Shortly before noon Rev Stover read the tenth chapter of Job, followed by a prayer by Rev Hall, followed by the hymn Rock Of Ages.

Then a black cap was drawn over the head of William Clark. His arms were pinned behind him. After descending the gallows the Sheriff called out "William J. Clark, do you still live?" to which Clark replied "I live!"

At 12:06 pm, Clark was dropped. His body was removed from the gallows thirty minutes later, at which time he was pronounced dead by three doctors. His body was placed in the coffin, then taken out to the front of the jail for the crowd to view, before being buried at the poor house farm east of Danville.

A Danville paper reported that upon hearing the gallows in the jail yard drop, Mary Twiggs sobbed loudly in despair.

The Execution Of Mary Twiggs

In early September of 1858, gallows had been constructed at the planing mill in Danville. A bag filled with mud was used to test it's efficiency. The evening before she was to be hanged, Mary Twiggs knelt down beside her bed and called audibly upon Jesus to save her immortal soul.

Three women, Mrs. Ware, Mrs. Unger & Mrs. Ephlin stayed at the prison with her that night, and joined her in prayer.

Mrs. Ephlin questioned Mary repeatedly, urging her to confess her sins, but Mary would only reply "Judge not lest ye be judged", as she continued to plead innocent of the crimes.

That evening, Mrs. Twiggs two young children were permitted to spend the night at the prison with their mother as well. When the children awoke that morning, Mary dressed them for the last time. She brushed their hair, and wiped the tears from their faces. Mrs. Ephlin, who was in the cell with Mrs. Twiggs, gave detailed accounts of Mrs. Twiggs last hours to the local papers.

Mary's brother Samuel arrived at the prison later that morning. Mary was heard telling him "We do not see what Jesus sees. If He was only where now to tell, He would tell you that I am innocent."

A host of ministers were on hand the the morning of the execution. They prayed with her, and after reading the 51st psalm, they sang a hymn chosen by Mary, "Oh That I Had Some Humble Place Where I Might Hide From Sorrow." Then the 23rd psalm was read.

Rev. Harden warning Mary of the consequences of deceit in her last minutes on earth, then asked if she was guilty or innocent. Mary continued to stress her innocence.

At 10 minutes past 10 on Friday morning, October 22 1858, after a few last prayer, Mary Twiggs followed the same path as William Clark had walked a month earlier, for the same crime. Wearing a black dress given to her by the sheriffs wife, she walked arm in arm with Rev Harden and the sheriff, crying loudly the entire way. She climbed the platform, and was seated on a chair. Rev Stover read the 15th chapter of Luke, with Mary continuing to weep.

When given the opportunity to speak, Mary was much more brief than William had been. She said simply that her Savior had died for her, and she did not fear death, that she had nothing to regret, and that she had never seen or knew anything about the poisoning of Catherine Ann Clark, nor her husband.

Rev Harden said a prayer, and then the ministers on the platform all said their goodbyes. Mary thanked them for their kindness. Then the sheriff pulled the black cap over Mary's head, pinioned her arms, and adjusted the rope around her neck.

As the final preparations were being made, Mary cried out repeatedly "I die innocent, I am not guilty!"

Sheriff Young then asked "Mary Twiggs, are you still alive?" She answered, "yes sir, I am" and then the drop fell and Mary Twiggs was "ushered into eternity".

After hanging for thirty eight minutes, her body was lowered into a coffin and she was pronounced dead

The doors of the jail yard were then thrown open, and the crowd that had been outside all morning rushed in to get a glimpse of her body.

Again, sheriff's deputies sworn in for the day, and the two military units, were on hand to control the crowd of spectators.

Mary's brother Samuel McClintock took the body to his sister to a farm in Mayberry Township for burial.

William Clark and Mary Twiggs were the first, and last, executions in Montour County.

Guilty, Or Innocent?

163 years later, it's impossible to know for sure. Clark inferred that a neighbor, Mrs. McMullen may have poisoned his wife and friend.

Mary claimed that her husband was so afraid of Dan McMullen that he wanted to move to Philadelphia to get away from him.

On Easter Sunday McMullen sent his daughter to ask Twiggs to come to the house, to sort out their differences. Twiggs and Clark both went to the McMullen home. When Twiggs returned to his own home, he sat down at the dinner table and was ill.

Days later, with Twiggs still sick in bed, McMullen stopped by. He said "Nothing ails you but ague [a "fevering or shivering fit"] and here is some medicine that cures ague without fail." David took the medicine, but got no better. In fact, he was worse until he died.

Rev Yeoman however, in a letter to the governor, appears to have believed Clark was guilty. He had refused to administer communion to Clark, " unsure of his spiritual standing." (Many of Yeoman's writings and correspondence can be found in the archives at Lafayette college, and in a variety of online forums that discuss the 1858 murders. He kept notes on all of his meetings with Mary Twiggs)

Mary Twiggs, when asked about Clarks innocence, said:

"I don't know anything at all about Clark, whether he is guilty or innocent. I never knew anything bad about him, as if he would poison his wife or my husband. I did not like him all together, not that I saw anything very ill about him, but he was light and trifling like, many time and acted foolish."

She went on to say that she never saw anything our of the way between him and his wife, and she had no belief that Clark had any particular affection for her. "He never had his hands on me the way that those witnesses swore. They were mistaken about all of that."

Two weeks before Mary's execution, the judge discussed her case with Governor William F. Packer. The judge felt strongly that the evidence during her trial did not warrant a guilty verdict.

In fact, there was a concerted effort in the community to have her pardoned. Rev. Yeoman wrote to the Governor as well, urging him to pardon Mary Twiggs. [Governor William F. Packer has worked as a printers apprentice at the Sunbury Public Inquirer. He studied in Williamsport, and was once the owner and editor of the Lycoming Gazette. He also served as superintendent of the West Branch Canal. He would have been well familiar with this area of the state.]

Petitions were circulated throughout the Montour Iron Works, including a letter from the the owners JP & John Grove, all stating that the evidence at trial had not been sufficient to convict, and urging the governor to grant her pardon. Newspapers throughout the nation criticized Danville's decision to hang the woman, when so many felt there was a possibility of her innocence.

A letter from Rev Yeomans pleaded for her pardon as well. He stated his belief that Mary was of feeble mind and may have been "victim and tool" of a stronger mind. Rev Yeomans seems to have not been convinced of Clarks innocence, but he did not believe Mary was involved in the murders.

The Wisconsin Democrat reported: "Mrs. Mary Twiggs was recently hung at Danville, Pennsylvania, for the supposed murder of Mrs. Clark. The papers state public opinion was divided on her guilt. It is bad enough to hand any person, but to hand a woman whose offense is not so clear, but that public opinion is divided with reference to her guilt, is an act of reckless barbarism, sufficient to disgrace any people."

|

| 1903 |

READ MORE

===========

A horrible case of supposed wife poisoning, has just been revealed at Danville, caused by the death, under suspicious circumstances, of Mrs. Catharine Ann Clark, on Saturday the 9th May. It having been ascertained that her husband, a peddler, named William Clark, had purchased, on several occasions previously, both arsenic and strychnine, in order, as he alleged, to poison rats, and her sudden death soon after, suspicion of foul play was created. Clark was arrested and a Coroner's jury summoned to investigate the cause of her death. The husband of a Mrs. Twiggs died about three weeks since, under similar circumstances, and for certain reasons suspicion rests upon her as being an accomplice of Clark's. She has been arrested. The body of Mr. Twiggs will probably be disinterred this evening (12th) for medical examination.

William Clarks children were to be taken in by Alexander Clark, Williams younger brother.

Mary Twiggs children were to be taken in by her brother, Samuel McClintock.

The Danville Poor House Farm land is now Memorial Park. There are no marked graves, only a memorial marker on the site.

No comments:

Post a Comment

I'll read the comments and approve them to post as soon as I can! Thanks for stopping by!