THE BIG RUNAWAY--FORT MUNCY.

NEWS OF THE WYOMING MASSACRE--SETTLERS ORDERED TO FLEE TO FORT AUGUSTA FOR SAFETY--GREAT EXODUS FROM THE VALLEY--CLOSELY FOLLOWED BY INDIANS WHO DEVASTATED THE ENTIRE VALLEY--SHORTAGE OF FOOD IN THE FORT--LOCAL EFFECT OF THE BATTLE OF MONMOUTH--TROOPS ARRIVE--BUILDING OF FORT MUNCY--ANOTHER INDIAN RAID--FORT MUNCY DESTROYED--CIVIL AFFAIRS DEMORALIZED--ENGLISH INFLUENCE AMONG INDIANS.

When the details of the horrible massacre at Wyoming in 1778 began to drift into the West Branch Valley the inhabitants were filled with apprehension and alarm. Many of the reports were exaggerated but enough was known to indicate that between 150 and 300 persons had been killed and no one knew when or where the next blow would be struck. The settlers determined to take no chances and they, therefore, prepared for a general exodus of the valley.

Orders had been sent to Colonel William Hepburn in command of the militia to direct the inhabitants to leave and repair to Fort Augusta at Sunbury. Word was carried to the outlying districts by Robert Covenhoven and a young millwright in the employ of Andrew Culbertson at his mill at the mouth of Mosquito Creek. They proceeded up the river by way of the crest of the Bald Eagle Mountains, so as not to be seen by the Indians that might be lurking along the flats, and continued on as far as Fort Antes, opposite the mouth of Pine Creek, and from there word was passed on up to Fort Horn at the present Pine Station on the Pennsylvania Railroad. From there the inhabitants above and in the vicinity of Lock Haven were notified.

Then followed a scene that has no parallel in the history of the United States. The land was filled with growing grain that was ripe for the harvest. Many of the settlers had just finished building their places of abode. Outbuildings had barely been completed and the people were in a state in which they could see a little rest and leisure ahead of them after the hardships incident to the settlement of the new country and blazing the way for an advancing civilization.

They were ordered to abandon everything and proceed down the river to Fort Augusta with all possible haste. Rafts and flat boats, canoes and all other kinds of river craft were hastily assembled and all the portable goods, horses, cattle, household utensils and other articles placed thereon. Boxes and barrels were lined along the sides to provide some sort of protection for the women and children. Such articles as were too bulky to be placed on the nondescript river craft were buried and the place well marked. All available provisions were assembled and every preparation made for the trip down the river. Fortunately, the weather was warm and there was no need for protection from the cold.

The wildest rumors were afloat and fear sat upon every countenance. The steadying influence of such men as Robert Covenhoven and his associates served to prevent a panic and the flotilla of women and children began its perilous descent of the river. The men walked along the shore to prevent possible attacks from Indians and many of them drove their cattle and horses ahead of them.

As they proceeded, the crowd was augmented by others further down who joined the fleeing people when the flotilla reached them. When night came part of the contingent following the shores were placed on board the craft to enable them to get a little sleep while the others walked along the banks obtaining a constant vigil. These men were relieved from time to time and others took their places. In this way the Journey to Fort Augusta was made and the people were none too soon in getting away for they were followed closely by marauding bands of Indians who burned and destroyed everything in their path.

As the fleeing settlers looked back on the places where their homes once stood they could see a sea of flame following them, the tongues of which were lapping up their deserted houses and waving grain fields. The torch was applied indiscriminately and nothing was left that was combustible. When the havoc was finished the beautiful valley was a desert of charred destruction.

The last contingent of the fleeing inhabitants reached Fort Augusta by the ninth of July, 1778 and then another difficulty confronted them. Their departure from the valley had been sudden and their arrival at Fort Augusta was unexpected. The problem of how to feed these new accessions to the overcrowded numbers already at the fort became a serious one and urgent representations were immediately sent to the authorities at both Harrisburg and Philadelphia, reciting the dire need of these people, and begging that sufficient food be provided for them to satisfy their immediate necessities. There was food sufficient in the lower counties but the problem was largely one of transportation.

Appeals were made to the citizens of Berks and Lancaster counties for assistance in this emergency and it was not long before food began to pour into Fort Augusta to relieve the precarious condition of the refugees.

Gradually those who had been driven out of the valley began to return to their homes or what was left of them. Small bands of settlers were organized and well officered. These followed up the roving bands of Indians and drove them further north, As the panic began to subside and confidence was restored more of the refugees returned. They found nothing but ashes and some still smoking ruins from Muncy to Antes Fort, a distance of twenty-eight miles. The Wallis mansion at Halls, and Fort Antes, at the mouth of Pine Creek, were the only buildings left standing and these were so substantially built that they resisted the effects of the torch.

After the battle of Monmouth was won and General Clinton driven out of New Jersey, General Washington was able to release some portions of his army and send them to the aid of the hardy frontiersmen of the West Branch Valley. Colonel Daniel Brodhead was dispatched to the Lycoming County section with 125 men and his coming not only inspired confidence but also caused consternation among the Indians who quickly retreated before his advance. Colonel Brodhead only remained for a few weeks, but during his short stay his presence, and that of his troops, had a salutary effect upon both the whites and the red men. He was succeeded by Colonel Thomas Hartley, an officer of considerable ability and reputation, who brought a detachment of militia to the neighborhood of Muncy farms, the property of Samuel Wallis. Hartley was quick to see the importance of this point for a fortification and reinforced by the representations of Wallis, strongly urged upon the authorities the necessity of erecting a strong defensive post at this strategic point. His recommendation soon bore fruit and the building of Fort Muncy was decided upon. It is probable that some sort of defensive work existed at the Muncy farms of Samuel Wallis from the time of the building of his mansion in 1769 and these, no doubt, were destroyed at the time of the "Big Runaway."

The many large tributaries of the West Branch of the Susquehanna River flowing into it from the north, afforded excellent opportunities for the Indians to float down them in their canoes and fall upon the unsuspecting settlers and the necessity Of a central point of concentration, with sufficient strength to resist attack, was, therefore, strongly felt.

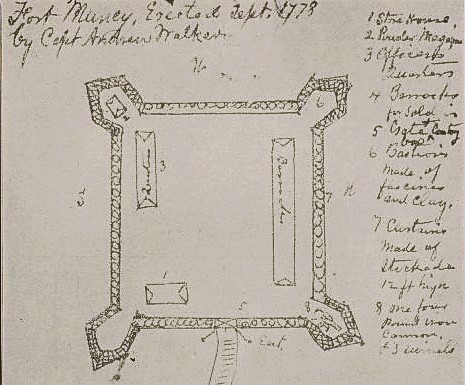

The building of Fort Muncy having been decided upon, Captain Andrew Walker was directed to take his company to that Point and erect the fortification at the earliest possible moment. The site selected was on a knoll a short distance from the Wallis mansion at a point where the cut of the Reading Railroad above where Halls Station is now located.

Work on the fort was begun about the first of August, 1778 and so rapidly was it pushed that by the first of September it was practically completed and ready for occupancy. Colonel Hartley was warm in his praise of Captain Walker and his men and in a letter to the supreme executive council said that he had never seen so much work done in so short a time.

The exact dimensions of Fort Muncy are not known, but it occupied considerable ground. It consisted of bastions made of fascines and clay, and curtains of stockades, twelve feet high. It contained officers' quarters, storehouse and powder magazine and was mounted with one four pound iron cannon and three swivel guns. A covered walk at the rear, or on the side toward the river, led to a never-failing spring of water. That it could accommodate 150 to 200 men is attested by the fact that Colonel Hartley had that many quartered there at the time he started on his expedition to Tioga Point.

Fort Muncy was used as a place of refuge by the inhabitants of Muncy Valley on more than one occasion. It was the most important fortification in Central Pennsylvania north of Fort Augusta and the only one erected on either the North or West Branches of the Susquehanna River by authority of the province.

In the summer of 1779 another runaway occurred in the valley, not as extensive as that of the year before, but the Indians again swept down the river and its tributaries in such strength that many of the inhabitants were forced to leave on short notice and numerous buildings were again burned, among them Fort Muncy. Whether any part of it was left standing is unknown but it is quite certain that it was rebuilt, for Moses Van Campen, the celebrated frontiersman and Indian scout, mentions in a letter that he visited it as late as the year 1782. Whether it was again destroyed is also unknown, but no traces of it now exist and the chances are that, after the close of the Revolutionary war when it was no longer needed for military purposes, it was allowed to fall into decay.

During its existence it was not only the rallying point for the settlers in case of danger, but it was also used as a storehouse for goods needed by the inhabitants and it was from it that ammunition, guns and other supplies were issued. It was the general distributing point for everything in the way of supplies that the people were in need of. Close to it also was a grist mill, owned and operated by Samuel Wallis, to which people from all over the Muncy Valley brought their grain to be ground.

Next to a fortification for their protection from Indians, a grist mill was the most important adjunct to an infant settlement. Food was a necessity and bread was the most important food. Machinery for grinding flour was, therefore, almost as essential to the people as a defensive work for their physical safety. Hence the appropriateness of having a grist mill located within the defensive radius of the guns of the fort.

Fort Muncy was located on open ground with a dense growth of timber in the rear which extended to the river, but on the north and east there was cleared land for a considerable distance which afforded an uninterrupted outlook up Muncy Creek. A better situation for a fortification of its kind would be hard to find.

One of the greatest troubles experienced by the inhabitants after their return to the valley, following the Great Runaway, was the demoralized condition of civil affairs. The courts had virtually ceased to exist. There was no attorney to prosecute criminals and business was at a standstill. For two successive meetings of the regular courts no prosecuting attorney had appeared and the supreme executive council was so notified. A six months' suspension of justice had caused some of the

People to become licentious, proprietors of tippling houses and promoters of vice and immorality became bolder and at least two charged with murder were still held in jail after six months without having been brought to trial.

This condition gradually righted itself after the inhabitants gathered up the tangled skeins where they dropped them in their precipitate flight from the valley early in the summer. Order was slowly brought out of the chaos and the inherent adaptability of the American people for self government began to assert itself. By the following spring conditions had returned to normal.

Following their chastisement at the hands of Colonel Hartley the Indians remained comparatively peaceful during the late fall and winter of 1778 and few of the settlers were molested. It seemed as though peace had come to stay and this condition of affairs would probably have continued had the Indians been left alone. But they were a constant prey to the machinations of the English. Their imaginations were excited by tales of oppression and greed on the part of the colonists and they were made to believe that if the Americans were able to win their independence the lands of the Indian would be confiscated and he would be driven from the country which he had inherited from his forefathers. Gradually the savages grew bolder and forays into the settlements of the whites became more numerous.

=================

No comments:

Post a Comment

I'll read the comments and approve them to post as soon as I can! Thanks for stopping by!